The UK government has formally abandoned plans for a controversial “exit tax” and has pulled back from a rise in income tax, marking two major reversals less than two weeks before the 26 November Budget.

The decisions follow strong opposition from the tech sector, wealthy individuals, and segments of the Labour Party, as Treasury officials scramble to fill a multibillion-pound fiscal shortfall without breaching election pledges or spooking investors.

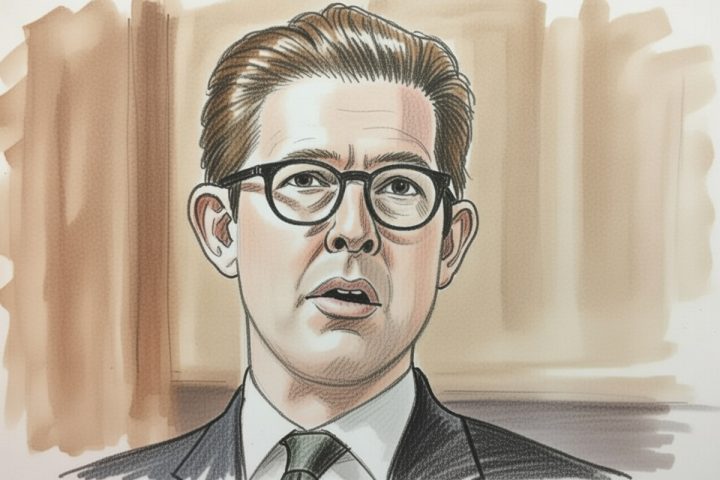

The withdrawal of the exit tax confirmed by the Telegraph, and later by Dom Hallas of the Startup Coalition after more than 1,500 founders and investors signed a coordinated letter to the Treasury, came shortly before reports emerged that Chancellor Rachel Reeves had also ruled out raising income tax rates.

Instead, the government is weighing adjustments to tax thresholds and a series of smaller measures aimed at raising revenue while avoiding overt manifesto breaches.

The exit tax proposal would have applied capital gains tax to individuals leaving the UK, mirroring policies used in several European jurisdictions.

The Treasury had estimated the measure could raise around £2 billion, part of what officials describe as a roughly £30 billion gap in the public finances.

But internal analysis reportedly concluded that the risks outweighed the benefits, particularly the prospect of accelerated wealth flight.

Business pushback was swift. Tech founders argued the proposal would discourage entrepreneurship and deter international talent.

Hallas, director of the Startup Coalition, announced late on Thursday that the government had “ruled out an exit tax,” crediting an unusually rapid mobilisation across the UK tech ecosystem.

Further pressure came from high-profile entrepreneurs. Media reports highlighted that Herman Narula, chief executive of Improbable, had been preparing to relocate to Dubai in anticipation of the measure.

His public criticism added to concerns already raised by data from Henley & Partners, which forecasts a net outflow of 16,500 millionaires from the UK in 2025, its steepest on record.

Senior financiers and property magnates have departed in recent months, including Goldman Sachs’s Richard Gnodde and investors Nassef Sawiris and the Livingstone brothers, fuelling fears that a punitive tax change could accelerate an existing trend.

Income tax reconsidered

The Treasury’s retreat from raising income tax follows similar political and economic considerations.

According to the Financial Times, the Prime Minister and Chancellor informed the Office for Budget Responsibility on Wednesday that rate increases were no longer under consideration, averting a manifesto breach after mounting criticism from within Labour.

Instead, changes to the income tax thresholds, often referred to as “fiscal drag”, remain under active review.

Adjusting thresholds would increase the tax burden as wages rise without altering headline rates, a more politically subtle mechanism used previously by Conservative chancellors.

Business leaders, acutely sensitive to signals of policy direction, are now focused on whether the government will offer reassurances to counteract uncertainty.

Industry groups have stressed the importance of predictable, long-term frameworks for capital investment, especially in sectors such as technology, finance, and life sciences