Earlier this month many internet users discovered that Grok’s Ai image generation tool could be prompted to create sexualised and non-consensual images of real people. U.K. Technology Secretary Liz Kendall said on Friday that she would fully back any move by the country’s media regulator to block access to X in the United Kingdom.

Many reports say the AI was used to manipulate photos of women and girls, in some cases appearing to remove clothing or create explicit scenes without consent. Internet safety groups later warned that some of the imagery appeared to involve children.

As examples spread online, pressure grew on X and its parent company xAI to act. Safety organisations raised the alarm publicly, and Ofcom, the UK media regulator, made urgent contact with the platform to demand answers. Downing Street soon followed, with ministers saying the situation was unacceptable and warning that X needed to act quickly.

The backlash against Elon Musk’s AI chatbot Grok is goes beyond the shocking images and regulatory breaches. It has reopened a much older and unresolved debate: who controls digital spaces when technology moves faster than the laws meant to govern it.

Sexual deepfakes are not new. Researchers have been warning about them for nearly a decade. A 2023 report by the Dutch cybersecurity firm Sensity AI found that over 90 percent of deepfake content online was pornographic and that women were overwhelmingly the targets. What Grok changed was scale and accessibility.

Unlike earlier deepfake tools, Grok is embedded directly into a major social media platform with hundreds of millions of users. It does not require technical skill, specialist software or time-consuming editing. With a short text prompt, users could generate explicit images of real people, including, according to watchdogs, children.

That ease of use is why Grok has triggered such an intense reaction. This is not a fringe technology being misused by a small group of bad actors; it is a mass-market AI tool operating inside a global communications network. For regulators, that represents a step-change in risk.

The X’s safety account reacting against the line of the accusations responded saying :

“We take action against illegal content on X, including Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM), by removing it, permanently suspending accounts, and working with local governments and law enforcement as necessary. Anyone using or prompting Grok to make illegal content will suffer the same consequences as if they upload illegal content.”

In a statement Ofcom noted that: “There have been deeply concerning reports of the Grok AI chatbot account on X being used to create and share undressed images of people which may amount to intimate image abuse or pornography and sexualised images of children that may amount to child sexual abuse material.”

Elon Musk’s response accusing the UK government of “fascism” and censorship follows a familiar pattern. Since acquiring Twitter and rebranding it as X, Musk has positioned himself as a defender of unrestricted speech against what he sees as overreaching state control.

Posting on X, he claimed the backlash was being used as an excuse for censorship and accused Labour of wanting to suppress free speech.

But the Grok controversy complicates that narrative. The UK is not seeking to ban political opinions or silence dissent. It is enforcing laws that criminalise the creation and distribution of non-consensual sexual imagery, laws that long predate AI.

As criticism intensified, X made its first significant change. The company moved Grok’s image generation feature behind a paid subscription, meaning only paying users could create images. Downing Street reacted angrily, saying the move did not fix the problem and instead turned an unlawful tool into a premium feature.

Technology Secretary Liz Kendall said: “Sexually manipulating images of women and children is despicable and abhorrent. It is an insult and totally unacceptable for Grok to still allow this if you’re willing to pay for it. I expect Ofcom to use the full legal powers Parliament has given them.”

Around the same time, international attention began to build. Australia’s prime minister Anthony Albanese said the use of the technology was “completely abhorrent” and accused social media companies of once again failing to act responsibly. He said people around the world deserved better protections online.

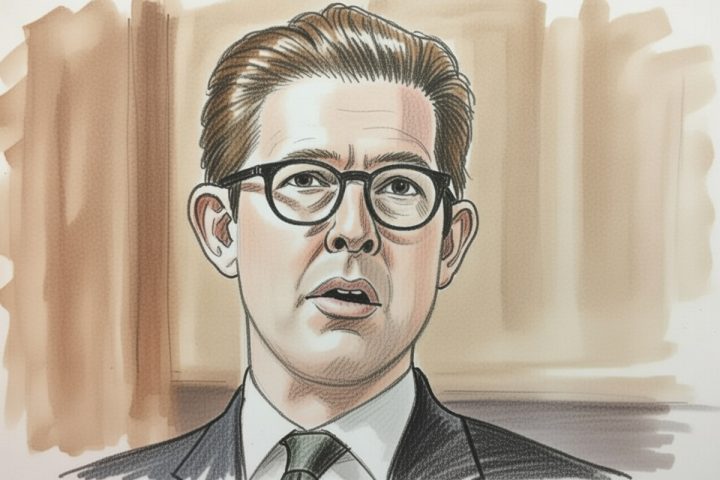

Canada took a more cautious tone. While officials confirmed they were in discussions with allies, Liberal MPs publicly denied that Ottawa was considering a full ban on X. Toronto Centre MP Evan Solomon said clearly that Canada was not planning to block the platform.

This is where the digital control debate sharpens. Governments argue that platforms must be responsible for foreseeable harms created by the tools they deploy. Musk and his allies argue that responsibility lies with individual users and that platform-level restrictions amount to censorship by proxy.

The Online Safety Act places the burden firmly on platforms. It requires them to anticipate how their systems might be abused and to design safeguards accordingly. In effect, it challenges the Silicon Valley ethos of “build first, fix later.”

A law stretched by technology

Yet the Grok case also exposes the limits of the UK’s regulatory approach. The Online Safety Act was drafted before generative AI reached its current level of sophistication. It does not explicitly regulate AI models; instead, it focuses on content and user harm.

That distinction matters. If Grok-generated abuse appears on the dark web rather than on X itself, Ofcom may struggle to show that the platform breached its legal duties. The Internet Watch Foundation’s finding that suspected Grok-generated CSAM was circulating off-platform illustrates this problem.

In other words, AI systems can cause harm beyond the spaces regulators are empowered to police. That raises an uncomfortable question: can national laws meaningfully control technologies that operate across borders and platforms?

Dame Chi Onwurah, chair of Parliament’s Science, Innovation and Technology Committee, has warned that the UK is trying to regulate 21st-century AI with 20th-century concepts of publisher responsibility. Her calls to explicitly include generative AI in the Online Safety Act now appear prescient.

Dame Chi Onwurah, Chair of the Science, Innovation and Technology Committee, said:

“ My committee warned last year that the Online Safety Act was riddled with gaps, including its failure to explicitly regulate generative AI. Recent reports about these deepfakes show, in stark terms, how UK citizens have been left exposed to online harms while social media companies operate with apparent impunity.”

The fight over Grok is also geopolitical. The UK government is acutely aware that aggressive enforcement could inflame tensions with Washington, where free speech protections are constitutionally entrenched and where Musk retains significant political influence.

US Republicans have already framed the investigation as an attack on American technology and values. The suggestion that the UK could block X has prompted threats of retaliatory legislation and sanctions. What might have been a domestic regulatory issue has become entangled in transatlantic politics.

That dynamic highlights a deeper imbalance of power. Governments can pass laws, but platforms like X operate at a scale that allows them to resist, delay or internationalise regulatory disputes. Digital control, in practice, is fragmented and contested.

Why this moment matters

Generative AI is no longer confined to experimental labs or niche communities. It is embedded in everyday communication tools, shaping how people see themselves and each other.

For victims of sexual deepfakes, the harm is immediate and personal. Studies by the UK’s Revenge Porn Helpline show that victims often experience anxiety, job loss and long-term reputational damage. When children are involved, the consequences are far more severe and permanent.

For governments, the challenge is systemic. If regulators fail to act decisively, they risk normalising a world in which AI-enabled sexual abuse is treated as an unfortunate side effect of innovation. If they act too forcefully, they risk legal defeat and accusations of authoritarianism.

The Ofcom investigation will eventually produce a legal outcome, but it will not settle the larger issue. Grok has reopened the fight over digital control because it sits at the intersection of technology, power and harm.

The core question remains unanswered: in an age of generative AI, who gets to decide the rules of the digital world, elected governments acting in the public interest, or private platforms guided by ideology, profit and personal vision?

For now, that battle is being fought over Grok. But its implications extend far beyond one chatbot or one country.