London-based Fuse Energy has reached a $5bn (£3.7bn) valuation after raising $70m (£52.3m) in a funding round led by Balderton Capital and Lowercarbon Capital, the company said this week. The fresh capital will be used to push Fuse’s expansion beyond the UK and to speed up the rollout of new products, as it looks to scale its integrated energy model across more markets.

For some, the deal will be read as another vote of confidence in Europe’s energy transition. For others, particularly incumbent utilities, whether privately run or state-owned, it lands less comfortably.

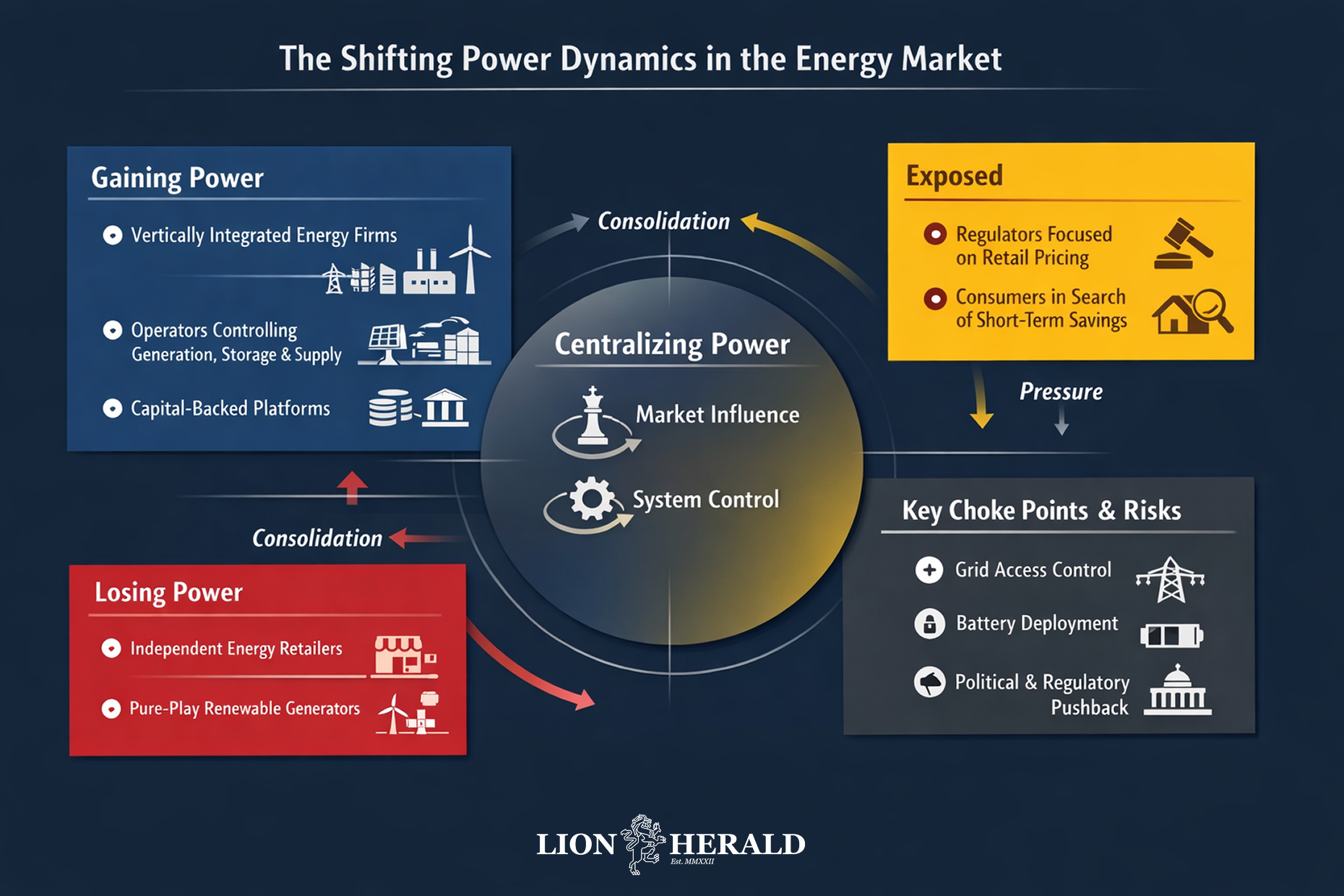

Fuse’s rise suggests that the competitive edge in energy is shifting. The advantage is no longer in renewables alone, but in how generation, infrastructure and customer relationships are stitched together. Vertical integration, rather than scale for its own sake, is emerging as the new moat.

In today’s briefing let us explore this.

Europe’s energy system is not a single market. It is a layered infrastructure stack, made by generation (renewables, legacy power), storage and flexibility (batteries, grid balancing), Trading and wholesale markets but also retail supply and billing without forgetting

regulatory and grid constraints.

Historically, these layers have been fragmented across different firms, each optimizing locally and extracting margin at handoff points. The result has been high consumer prices, slow innovation, and limited system-level efficiency, especially visible during energy shocks following the war in Ukraine.

Fuse Energy is attempting to collapse this stack into a single, vertically integrated operator.

With Fuse Energy reaching a reported $5bn valuation in its third year, the structural change is more important, and it should be noticed and considered seriously.

Capital is flowing aggressively toward vertically integrated energy operators, not just asset owners or software layers.

It looks like investors are underwriting the belief that system-level control, not marginal efficiency gains, is where durable advantage now lies in energy.

From a simple spectator perspective, (at least from us at Lion herald) this marks a shift away from the assumption that energy innovation happens primarily through individual renewable assets,

retail pricing competition or incremental grid reform.

Instead, as experts would agree, it looks like the bet shifted to the fact that owning multiple layers of the energy stack is the only way to materially reduce costs and manage volatility, from now going forward.

At first glance, vertically integrated players like Fuse look straightforwardly positive.

When you collapse generation, trading, supply, and sometimes even hardware into one entity, you remove layers of margin. There are fewer middlemen. Fewer contracts. Fewer handoffs. That alone lets you price more aggressively than incumbents who are still operating inside a fragmented system.

So in the near term, consumers feel this in very practical ways, bills are lower, pricing is simpler and volatility feels more manageable.

Fuse talks about roughly 10% lower prices. That doesn’t sound revolutionary, but for households, it’s real money. And politically, it matters. Lower energy prices buy goodwill, patience, and legitimacy.

But once you zoom out a little, the dynamics shift.

As vertically integrated players scale, they don’t just compete on price, they change the economics of survival for everyone else.

Independent retailers, who don’t own generation, start getting squeezed. Independent generators, who rely on long-term power purchase agreements, find themselves negotiating with fewer, more powerful counterparties.

Margins that used to be spread across the system start concentrating inside a smaller number of platforms.

Wholesale markets begin to behave differently too. When the same entities control both supply and generation, market liquidity thins. Price signals change. Flexibility becomes internalized rather than traded.

This is the point where the system becomes less competitive in appearance, but more efficient in operation.

And that’s uncomfortable, because efficiency and competition are no longer aligned.

Clearly, operational excellence helps, but it’s not the driver. The driver is control, over assets, over flows, over coordination across the system.

In this scenario, lower prices are not only the result of better execution or clever technology. They are the result of power consolidation.

Winners and Losers

Now let’s talk explicitly about power, because this is the part that usually stays implicit. Markets change all the time. What matters is who gains leverage as they do.

The clear winners in this shift are vertically integrated energy companies with access to capital.

When a single operator controls generation, storage, trading, and the customer relationship, they’re no longer just participating in the market, they’re coordinating it. They decide where flexibility lives. They decide how volatility is absorbed. And they decide how value is distributed across the stack.

Access to capital is critical here. Vertical integration in energy is expensive. You need to finance assets years before they pay back. You need balance sheets that can absorb shocks. So power concentrates not just in integrated firms, but in well-capitalized ones.

And once a company controls both electrons and customers, both the physical flow of energy and the commercial relationship, it becomes very hard to dislodge. Switching costs rise. Negotiating leverage improves. Optionality increases.

That’s real power.

Next: who is losing power

On the other side of the equation are pure-play energy retailers.

These businesses sit at the edge of the system. They don’t control assets. They don’t control pricing inputs. They mostly compete on branding, customer service, and thin margins. In a vertically integrating world, that’s a fragile position.

They become price takers in a market increasingly shaped by players upstream.

Independent generators face a similar squeeze. Many of them rely on long-term power purchase agreements for stability. Those contracts made sense in a fragmented market. But as buyers consolidate, the balance of power in those negotiations shifts.

Fewer buyers. More standardized terms. Less flexibility.

What used to feel like stability starts to look like dependency.

The most interesting group here isn’t the winners or the losers, it’s those who are exposed.

Regulators, for example, often focus on competition where it’s most visible: the retail layer. Are prices fair? Are consumers switching providers? Is there enough choice?

But while attention stays there, integration is accelerating upstream, where leverage actually forms. By the time concentration becomes obvious at the retail level, the system underneath may already be locked in.

Consumers are exposed in a different way.

In the short term, they benefit. Lower bills matter. Simpler pricing matters. But those gains may come with a tradeoff that’s harder to see: fewer providers, less structural competition, and greater dependence on a small number of operators.

The risk isn’t exploitation tomorrow. It’s optionality disappearing over time.

What the market is getting wrong

At this point, it’s worth addressing what the market is getting wrong, because most confusion around energy innovation comes from importing the wrong mental models.

A lot of people look at companies like Fuse and conclude: this is about clean energy. Solar, wind, decarbonization.

That’s true, but it’s incomplete. Renewables are necessary. They are not sufficient.

What actually creates advantage here isn’t how clean the electrons are, but how well the system is coordinated. You can have the cleanest generation in the world and still run an expensive, fragile energy system if generation, storage, trading, and supply are all misaligned.

The real breakthrough is treating energy as a single, integrated system rather than a collection of disconnected assets.

If you focus only on cleanliness, you miss where leverage is forming.

The other most popular conclusion worth mentioning here is “Software is the differentiator”. This is a very common tech reflex.

People assume that because something feels modern, the moat must be software. Better dashboards. Smarter pricing. More automation.

Software absolutely helps. It makes coordination possible. It lowers operating costs. It improves execution. But it’s not the moat.

The moat in energy is physical and contractual, who owns generation assets, who controls grid access, who has long-term capital locked in at the right cost?

Software without assets is leverage without force. It improves efficiency, but it doesn’t shift power.

The companies that win are the ones where software sits on top of ownership and control, not the other way around.

And finally the wrong conclusion that you should definitely not ignore: “Energy disruption will look like fintech disruption”

This is probably the most dangerous analogy. Many of the people building and funding energy companies come from fintech, where vertical integration and software-first thinking worked spectacularly well.

But energy is not banking. Energy is heavier. Slower. More regulated. It’s tied to national security, industrial policy, and household stability. When things go wrong, governments intervene, and they intervene bluntly.

Vertical integration can work in energy, but it carries risks fintech has never faced such as political scrutiny, regulatory backlash and public accountability during crises.

You can’t “move fast and break things” when the thing you’re breaking is electricity.

These conclusions distort analysis, they lead to bad decisions. They cause investors to overestimate speed, founders to underestimate resistance, and policymakers to regulate the wrong layer of the system.

The bottom line

Fuse Energy’s $5bn valuation is a signal about where Europe’s energy system may be heading next. Vertical integration is no longer some edge strategy or niche experiment.

For well-capitalised players, it’s fast becoming the default. And that poses a genuine challenge to how energy in Europe has been structured for decades, not through deregulation or flashy new assets, but through the steady consolidation of control across the system.

Whether that shift turns out to be healthy or harmful isn’t something any single company can decide. It depends on the choices made around it. Regulators will need to ask what kind of efficiency they are willing to trade for what kind of competition.

Policymakers will have to weigh lower prices today against greater concentration tomorrow, and decide how much resilience should be designed into the system rather than left to market forces.

Even investors face a more complex question: are they backing long-term infrastructure builders, or quietly underwriting a new form of market power?

What Fuse has really done is force these questions into the open. And that, in itself, is disruptive. Europe’s energy future won’t be shaped only by how many renewables get built or how much carbon gets cut, but by who coordinates the system, who carries the risk, and who ultimately sets the terms.

If this moment pushes us to think harder, to explore alternative models, and to ask better questions before the system locks itself in, then this “threat” may also be an invitation, to rethink how energy should be owned, governed, and shared.