Global leaders are gathering in New Delhi for the AI Impact Summit this week, with countries arriving with noticeably different but overlapping ambitions. The United Kingdom has a message about public service transformation and global standards. India is welcoming everyone with something more structural, almost infrastructural, a plan to reshape who gets access to artificial intelligence in the first place.

The contrast here is not confrontational. If anything, according to analysts it shows how the AI race is evolving into multiple lanes rather than a single competition.

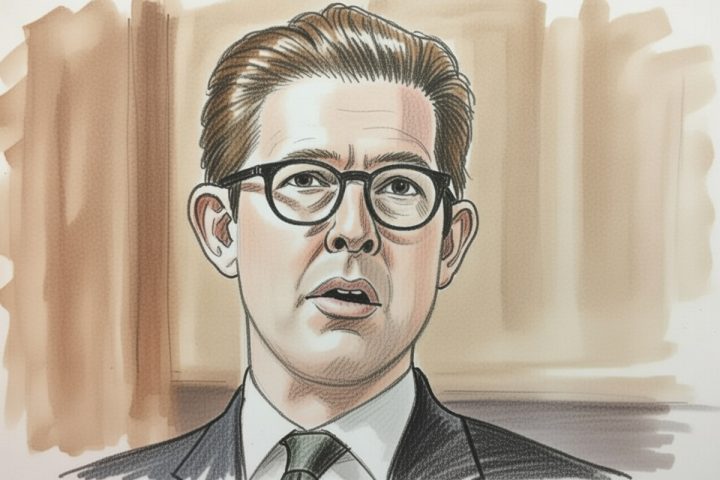

The UK delegation, led by Deputy Prime Minister David Lammy and AI Minister Kanishka Narayan, is focusing heavily on practical outcomes for citizens. The message was simple, AI should make everyday life better. Reducing hospital waiting times, improving government services, and creating jobs through AI deployment.

India’s pitch on the other hand, articulated by ministers including Jitin Prasada, is broader and arguably more ambitious. India wants to become what officials describe as an AI service backbone for the world, especially for developing nations. The focus here is not building applications, but creating affordable computing access, governance frameworks, and talent pipelines that other countries can rely on.

Different priorities, but both rooted in influence.

The event in New Delhi follows earlier global AI gatherings at Bletchley Park, Paris, and Seoul. Those meetings largely focused on safety and governance risks. This one feels more economic. More grounded in deployment.

Britain’s approach can be described as application first. Officials are positioning the country as a leader in AI innovation, regulation, and ethical frameworks while also promoting domestic benefits.

Lammy has been expected to discuss an African Language AI initiative that could support up to 40 languages. The idea is both humanitarian and strategic. Language access opens markets, and markets bring influence.

The UK is also leaning into partnerships. The visit builds on a trade agreement announced last year by Prime Minister Keir Starmer during a state visit to India.

There is also a political dimension. Talking about AI improving public services plays well domestically, where voters care more about healthcare waiting lists than semiconductor supply chains.

India’s plan looks different because it starts at a deeper layer of the technology stack.

Instead of subsidising hardware directly, the government is subsidising access to computing power. Officials say AI compute in India can cost roughly one third of what it does elsewhere.

The country is also leaning heavily on its experience with digital public infrastructure, systems like national payments and digital identity that already operate at population scale. The thinking seems to be that AI can follow the same model.

There is a strong geopolitical undertone too. India repeatedly emphasises support for the Global South. In a world where AI capabilities are concentrated in a few countries, offering affordable access could translate into significant international influence.

UK officials talk about AI creating opportunities and economic renewal. Indian policymakers seem to be focusing on skilling programmes, labour mobility, and linking training directly to income growth rather than certificates.

In my view what makes this moment interesting is not which country leads. One of the perspectives to monitor is whether multiple leadership models can coexist.

AI is often framed as a race dominated by the United States and China. But gatherings like this suggest a more complex future, where middle powers carve out specialised roles.

The UK wants to be the trusted innovator. India wants to be a scalable provider.

Both might succeed. Or both might discover that execution is much harder than vision. That part is still uncertain, and perhaps a bit messy.

What is clear is that AI diplomacy has begun to look a lot like economic diplomacy. And that means summits like this are no longer just about technology but more and more about power.