In the race to build artificial intelligence that truly “understands” how the world works, humans are still way ahead.

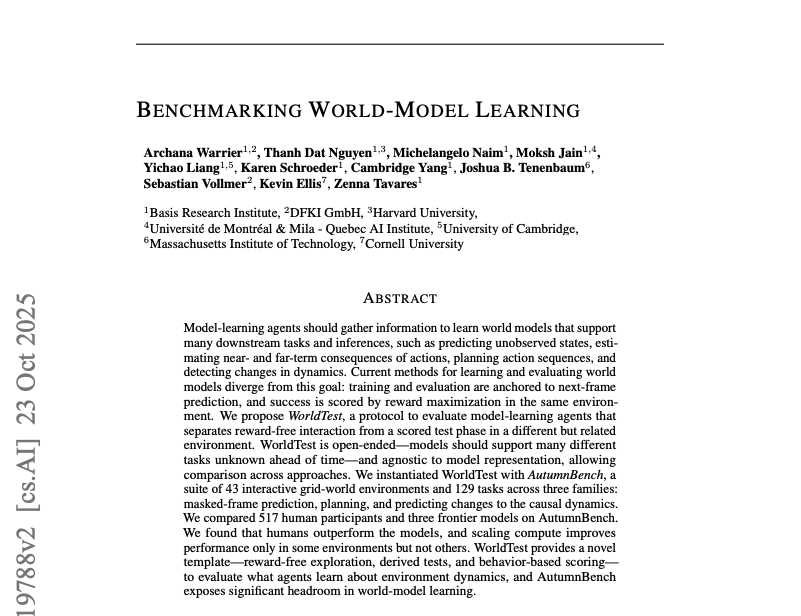

A new study introduces a comprehensive evaluation framework called WorldTest, paired with a suite of interactive environments named AutumnBench, and the results are sobering for AI developers: even the most advanced reasoning models, Anthropic’s Claude 4 Sonnet, Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro, and OpenAI’s o3, fall dramatically short of human performance when tested on basic but flexible world-modeling tasks.

The question at the center of the research was something far more fundamental: Can an AI learn how an environment works just by exploring it, without being told what to do, and then apply that understanding to solve new, unexpected problems?

According to the research team from Basis Research Institute, MIT, Harvard, Cornell, and other leading institutions, the answer is still a resounding no.

Imagine you’re cooking in your own kitchen. You know where the knives are, how long the water takes to boil, and what happens if you forget to turn off the stove.

Now imagine using a friend’s kitchen for the first time. You quickly spot differences, maybe the oven heats unevenly or the spices are in a different drawer, and adapt on the fly.

That mental map you’re using? Cognitive scientists call it a world model: a flexible, predictive internal representation of how things behave, interact, and change over time.

In AI, a world model is typically a learned function that predicts future states based on past actions and observations. Many researchers, including Yann LeCun, believe mastering world-model learning is essential to the next leap in artificial intelligence, beyond statistical pattern matching toward something closer to genuine reasoning.

But until now, there was no consistent, fair way to test whether AI systems are actually building useful world models, or just memorizing trajectories to maximize rewards.

Previous approaches to evaluating world models suffered from critical flaws:

- Non-interactive tests (like image or video reasoning puzzles) don’t let agents act or experiment.

- Reward-driven benchmarks (like Atari or Procgen) only measure how well an agent scores points in one specific task, not whether it understands the underlying rules.

- Representation-specific evaluations force models to output pixel predictions, programs, or graphs, making it impossible to fairly compare different AI architectures, or humans.

“We needed a framework that treats the agent as a black box,” explains the paper, “judging only by behavior, not internal structure.”

How WorldTest works: Learn first, test later

WorldTest separates learning from evaluation through a two-phase protocol:

- Interaction Phase: The agent explores a simulated environment without any rewards or goals. It can press buttons, move objects, reset the world—whatever it takes to figure out how things work. Think of this like a child playing with a new toy, forming hypotheses through trial and error.

- Test Phase: The system presents a new but related challenge, derived from the original environment. This could involve:

- Predicting hidden parts of a scene (Masked-Frame Prediction),

- Planning a sequence of actions to reach a goal (Planning), or

- Spotting when a familiar rule suddenly changes (Change Detection).

Crucially, the test environment is different from the one used for exploration, just like noticing your rental kitchen’s stove behaves oddly compared to your own.

This setup mimics real-world intelligence: learn general principles in one context, apply them flexibly in another.

To bring WorldTest to life, the team built AutumnBench, a collection of 43 grid-world environments coded in a custom language called Autumn. These range from simple logic puzzles to simulations of plant growth, sandcastles, game-like scenarios (including a version of Nim), and multi-agent systems.

Each environment spawns three distinct challenges, totaling 129 tasks designed to probe different facets of world understanding.

Human participants (517 screened individuals recruited via Prolific) and three frontier AI models were put through the same paces.

The results? Humans outperformed all AI models across every task type and nearly every environment.

- Average human score: 0.935 (on a 0–1 scale)

- Best AI model (o3): Significantly lower, with wide gaps in planning and change detection

- Even in environments where AI got lucky, performance was inconsistent and brittle

Why are humans so much better?

Two key behavioral differences emerged:

- Strategic Use of Resets: Humans used the “reset” button far more often, about 12.5% of their actions, suggesting they treated it as a tool for hypothesis testing: “What happens if I start over and try this differently?”

In contrast, AI models used resets in less than 7% of actions, often ignoring them entirely. Claude 4 Sonnet, for example, used resets or no-ops only 2.1% of the time. - Focused Exploration Over Time: Researchers measured how “targeted” agents became by tracking normalized perplexity, a metric of action randomness.

Humans quickly shifted from random poking to purposeful interaction, showing lower perplexity and lower area-under-the-curve (AUC) scores, signs of rapid, effective learning.

AI models, by comparison, remained relatively unfocused throughout.

“Humans treat reset as an experimental tool,” the paper notes. “Reasoning models… fail to recognize that resets and no-ops can be as or more valuable for testing hypotheses.”

Even more telling: AI models often failed to update their beliefs when confronted with contradictory evidence, especially in masked-frame prediction tasks. They clung to initial assumptions, even when observations clearly violated them

Bigger compute ≠ smarter AI

The team also tested whether throwing more computational resources at the problem helped. The answer: sometimes, but not reliably. They identified two sets of environments:

- Set A (25 environments): Performance improved with higher-cost models.

- Set B (18 environments): More resources made no difference—or even worsened performance.

This suggests that current models aren’t just underpowered; they’re missing core reasoning capabilities that scaling alone can’t fix.As the authors put it: “Human-level performance requires advances in metacognitive capabilities: strategic experimental design, better uncertainty quantification, and flexible belief updating.”

WorldTest is a new philosophy for evaluating intelligence. By decoupling exploration from reward, and testing generalization across modified environments, it offers a path toward assessing whether AI truly understands the world, rather than just optimizing for a score.

AutumnBench is publicly available at https://autumn.basis.ai , and the team encourages extensions, like testing tool substitution (“Can a wine bottle replace a rolling pin?”) or analogical reasoning.

For now, though, the message is clear: despite billions invested in AI, the humble human brain remains the gold standard for learning how the world works, one curious experiment at a time.